Is Hunting and Foraging the Future of Mankind?

Book Review by Ray Urbaniak

Paul Shepard was an environmentalist and wrote “Coming Home to the Pleistocene” just before his death in 1996. His wife, Florence Shepard, a Professor Emerita at the University of Utah, edited the book, which was published in 1998.

From: Paul Shepard, Wikipedia

Shepard's books have become landmark texts among ecologists and helped pave the way for the modern primitivist train of thought, the essential elements being that “civilization” itself runs counter to human nature - that human nature is a consciousness shaped by our evolution and our environment. We are, essentially, “beings of the Paleolithic.”

This is an extremely fascinating book! And although it is written from a Western perspective, this is what Native Peoples have been saying about the environment all along, including the interdependence of all animals and plants. We are all part of the web of life according to Native American spirituality.

In order to distill the essence of this influential book, I have selected a number of quotes that project the depth of thought and sense of urgency from the book.

“The Paleolithic or ‘Old Stone’ Age is not central to the origin of craftsmanship, since all hunters and gatherers have made more use of organic material than of flint. It just happens, however, that the evidence from stone—artifacts, pictographs, and petroglyphs—is our best source of information on the prehistory of speech, art, and narration.” (page 166)

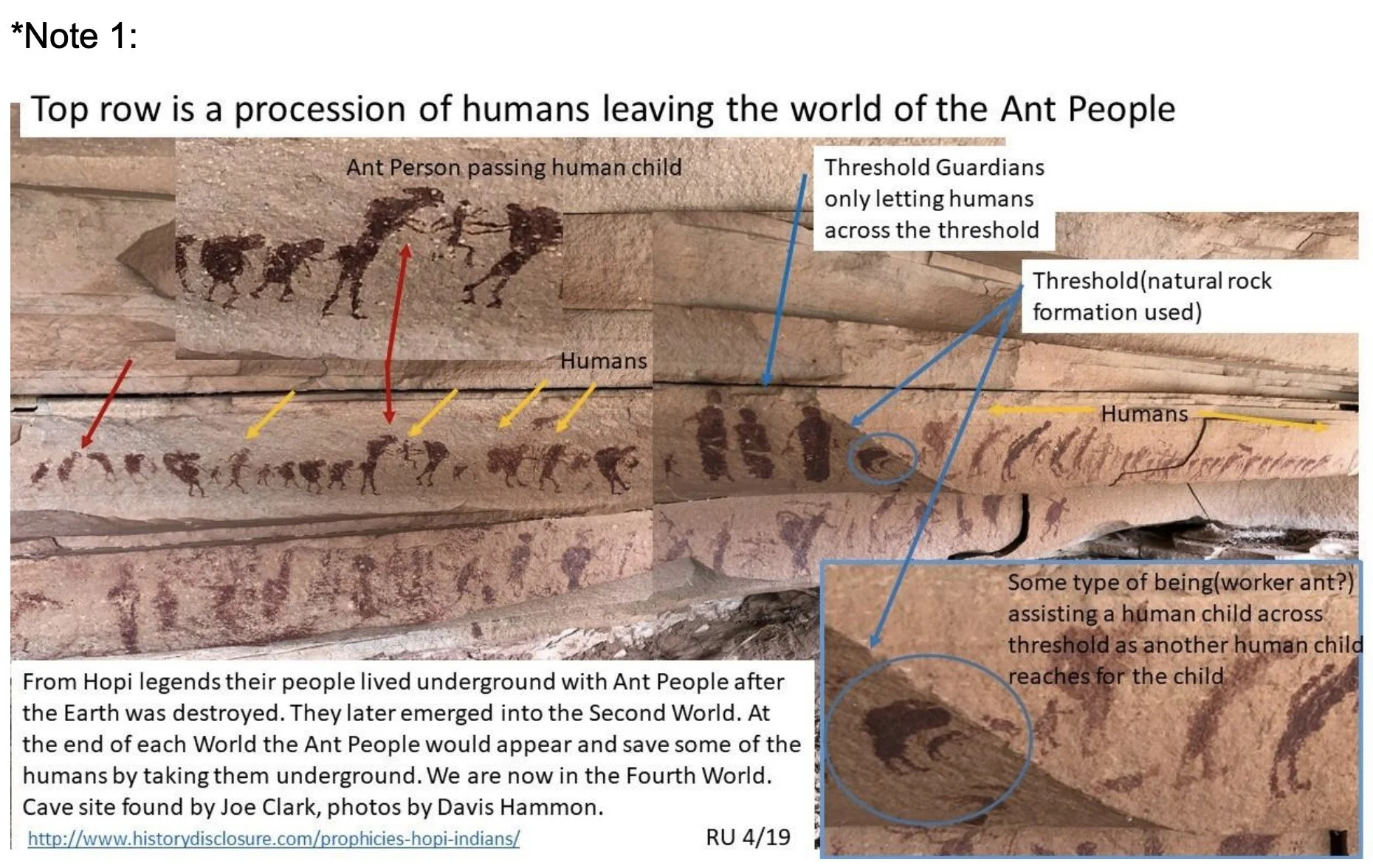

This is the reason why I have spent over 20 years studying petroglyphs and pictographs, including Ice Age Animals in rock art. I have identified and recorded nearly 80 Solstice and Equinox markers which Native Americans used to mark the passage of time and were used to tell when to conduct prayers and ceremonies around these points in time, such as Winter Solstice ceremonies to bring back the Sun to a higher point in the sky and longer days, assuring the renewal of life and abundance. I have also identified several myths depicted in rock art. One of the myths I have identified in rock art could be the origin of the Hopi emergence myth. I have included it at the end of the article. (*Note 1)

Pleistocene animal depictions, which I have recorded, as well as photos provided by others, include 29 Ice Age animal depictions, which are summarized in the November-December 2022 issue of the Pleistocene Coalition, pages 16-22.

The petroglyphs and pictographs I documented and have written about are a window into the spirituality and myths of Native Americans. They also offer a glimpse of the Ice Age animals they encountered and or recorded based on oral history. My work and beliefs tie in nicely with this book by Paul Shepard, hence my fascination with his book.

Paul Shepard was influenced by the theories of the social anthropologist Claude LéviStrauss. It should be noted that Lévi-Strauss also studied the Native Americans from South America, whom he had sympathy and respect for. “Claude Lévi-Strauss argued that the "savage" mind had the same structures as the "civilized" mind and that human characteristics are the same everywhere.” (Wikipedia, Claude Lévi-Strauss)

In my opinion, Paul Shepard, although influenced by Lévi-Strauss and others, possessed a passion that genuinely stems from his connection to nature and his experiences derived from living in harmony with nature.

“We, among all creatures, are in some ways the most free. Yet, even though blessed with wider choices than the other animals, we are not truly free to be immature, or for culture to neglect to mitigate our immaturity. That modern psychology has taken the wrong track is reflected in the popular narcissism of the self and the study of the personality as though adolescent self-absorption were normal in the context of the hubris and hedonism of our affluent society. Modern psychology, including ‘ecopsychology’ and ‘environmental psychology,’ tends to portray the self in terms of individual choices about beliefs, possessions, and affiliations rather than defining the self in terms of harmonious relations to others—including other species—and in terms of the ecological health of the planet.” (page 27)

“Peer groups are unimportant in a band of twenty-four in which there may be seven or eight children of mixed ages. And older children caring for younger children may have important ramifications that are not yet widely understood. With the primal people, there are no adolescent groups brought together for ceremonial initiation. (Adolescent in-groups and secret societies occur in competitive and warlike cultures, not among hunter/gatherers.) ‘Hanging out’ together of age-stratified youths may be one of the most destructive characteristics of our present culture. Without a childhood that has grounded them in the natural world, often without adults anticipating and properly monitoring and celebrating their transition into adulthood and understanding their idealism and need for spiritual experiences, youth often find themselves alone in this modern world. In age-specific gangs, they are ‘growing themselves up’ the best way they know how, often in a milieu of violence and power rather than in spiritual communion.” (page 44)

Paul Shepard was not a romanticist! He realized that the hunter-gatherer life was not an easy life, but he felt it was rewarding just the same, based on hunter-gatherer tribes living today, which he researched. He also knew that hunter-gatherers were equally subject to aggression, lying, stealing, etc. According to Paul, Native Peoples “are as complex, profoundly religious, creative, socially and politically astute, and ecologically knowledgeable as ourselves, or more so.” (page 3)

Killing in the face of death was reciprocity. “The hunt deals with the intense emotional and philosophical problems raised by the killing and facing one’s own death. It is not a problem for us simply as predatory carnivores, but as the occasional prey, and as an omnivore whose closest kindred species are also omnivores, conscious, sentient beings like ourselves.” (page 61)

Regarding Agriculture

“If there are slim days the !Kung San do not go hungry for long, compared to the northern Ghana farmers, says Lee, “There is still no evidence for a weight loss… even remotely approaching the magnitude of loss observed among agriculturalists.” (page 74)

“With irrigation, cultivation, and the rest of the routine round of obligatory labor, the human environment probably seemed in any one lifetime inevitable and unchanged. The ancient human acceptance and affirmation of a generous and gifting world was replaced by dreams of plenty in circumstances that made their fulfillment possible only in boom years. Domestication would create a catastrophic biology of nutritional deficiencies, alternating feast and famine, health and epidemic, peace and social conflict, all set in millennial rhythms of slowly collapsing ecosystems.” (page 83)

“But as people began to till the earth, other species were categorized as the enemy.” (page 85)

“War and warriorhood probably grew out of territorialism inherent in agriculture and its exclusionary attitudes and the necessity for expansion because of the decline of field fertility and the frictions and competitions of increased human density.” (page 86)

In foraging societies, “The child grows up wanting and owning very little, gaining familiarity with the means and joys of life.” (page 46)

I had an anthropology professor who lived for a time with a remote tribe in the Amazon. He said it was as full a life experience as anything our culture has to offer. I still remember this, after all these years, because I had the sense that he would rather be living with them than teaching the class.

“What was a good (and very highly specialized) brain for positioning a terrestrial primate in a Pleistocene niche is evidently maladapted for life in the throes of its own glut of people and barrenness of nature.” (page 134)

“The world is full of war, terrorism, social disintegration, poisoned air, and land. The soil that has accumulated for centuries is washing into the sea; the earth’s forests are being devastated. Virtually all the diseases of the past are with us in more virulent form, and new epidemics of psychic breakdown, dysfunctional families, and organic infection are upon us. The last benefits of the raiding of the earth by the affluent minority still give us an illusion of well-being in the midst of worldwide calamity.” (page 169)

“Ecologically, the Pleistocene asks that we free ourselves from domestication. In a better (but not other) world, there would be no monocrop agriculture, hybrid seeds, chemical fertilizers, or industrial pesticides.” (page 166)

Regarding Pastoralism and Cattle Herding

“Remembering that the opposite of wild is not civilized but domesticated” (page 145)

Wildness removed from animals by domestication means that they are no longer the same animals! Animals in zoos are no longer the same animals. “The shift toward pastoral monotheism drained sacredness from other forms of life and diminished the spirituality of lower beings, human or nonhuman.” (page 123)

“Their preoccupation with domestic animals and political strife, tighter male dominance, and the elevation of religious patriarchy to a sky god produced disastrous ideology and ecology. Where farmers destroyed only arable land, the hooves and teeth of ranging ungulates destroyed wildlands, upper water sheds, and whole forests.” (page 124)

“Animals would become ‘The Others’. Purposes of their own were not allowable, not even comprehensible. Our relationship to the nonhuman life on earth, a relationship lost with the Pleistocene, is no different than cherishing relationships we are capable of developing with humans who are very different from ourselves.” (page 129)

Combined effects of Agriculture and Pastoralism

“Wildness, pushed to the perimeters of human settlement during most of the ten millennia since the Pleistocene, has now begun to disappear from the earth, taking the world’s otherness of free plants and animals with it. The loss is usually spoken of in terms of ecosystems or the beauty of the world, but for humans, spiritually and psychologically, the true loss is internal. It is our own otherness within.” (page 143)

Göbekli Tepe (an anomaly)

The archeological discovery was brought to the world's attention by The Smithsonian Magazine in 2008. Two years later, Newsweek followed with a brief article. National Geographic carried the story on its cover in 2011.

Paul Shepard died in 1996, long before Göbekli Tepe was made public. I wonder how an 11,000 to 12,000-year-old structure built by people who some believe were the first agriculturalists would fit into his model of Pleistocene hunter/gatherers?

The author appears to believe that the Pleistocene was the high point of human development. Throughout the book, one gets the feeling that he believes that society will eventually crumble, and then we will “Come Home to the Pleistocene.”

At the end of the book, he lists 71 Aspects of a Pleistocene Paradigm, yet on page 173, he seems to deny talking about how bad things are and the imminent collapse of civilization. “Must we build a new twenty-first-century society corresponding to a hunter/gatherer culture? Of course not; humans do not consciously make cultures.”

He talks about creating a modern life around these 71 aspects of a Pleistocene Paradigm. But this is unlikely unless there is a collapse of civilization, leaving a much smaller population on earth, or his paradigm is just adapted by a cult following.

As you can see from the above quotes, he is very specific about how he feels that farming and pastoralism don’t work.

In the early 1970s, after two decades of activism, he became disillusioned with the environmental movement because very little progress was being made toward sustainability.

That was 50 years ago, when there were 4 billion people on the planet; we now have 8 billion people on the planet, and we have exponential acceleration of global warming, species extinction, pollution, etc. I can’t imagine what he would think if he were alive today.

Even if we were to rebuild after a collapse, we would most likely recreate what didn’t work. We are tool makers, and we use tools to make other tools, which include tools of mass destruction, genetic engineering, polluting chemicals, etc. Unfortunately, we can’t put the genie back in the bottle!

I wrote this book review with the hope that it will heighten awareness as to the extreme challenges facing us today to simply survive what is coming.

I encourage anyone interested in the late Pleistocene to read Paul’s book: “Coming Home to the Pleistocene.”